I noticed recently that WordCamp Nairobi is on the calendar for 1-2 November. Then I noticed their Camp slogan is “Beyond the Savannah: Connecting the Kenyan WordPress Community to the World”, and I thought “Yes! That’s so perfect for HeroPress!” So much so that it’s going to help drive the mission of HeroPress in the […]

Continue readingTag Archives: Call

Last Call for the 2023 State of Open Source Survey – WP Tavern

OpenLogic, a company that provides technical support for enterprise open source infrastructure, and the Open Source Initiative (OSI), the nonprofit stewards of the Open Source Definition (OSD, have collaborated to put together the 2023 State of Open Source Survey. The annual survey collects data from professionals to identify trends in the adoption and challenges of using […]

Continue readingOpen Meeting and Call for Feedback – WP Tavern

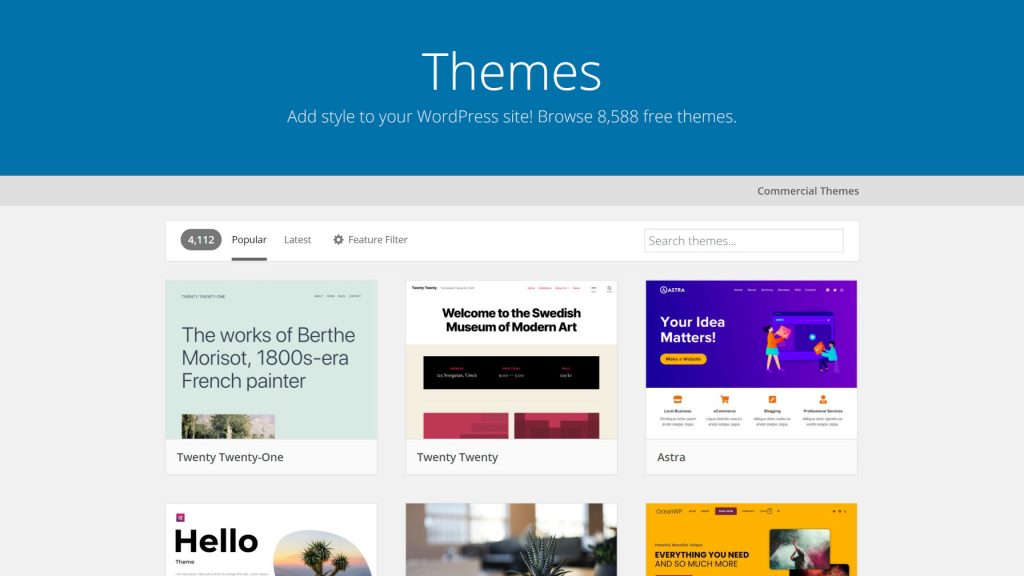

The WordPress.org Themes Team announced an open discussion and date for a Zoom meeting with theme authors. The team is proposing a new set of guidelines that reduces and simplifies what is currently in place. Comments on the proposal are open through July 26, and the meeting is set for July 28, 2 pm CET. […]

Continue readingA Developer-Centric Call for Testing Theme JSON Configuration – WP Tavern

Round #8 of the Full Site Editing (FSE) Outreach Program began yesterday. Instead of the user-centric call for testing features from the UI, program lead Anne McCarthy asks that volunteers dive into code. The new adventure is all about testing theme.json files. The twist is likely to limit the pool of usual volunteers. However, it […]

Continue reading