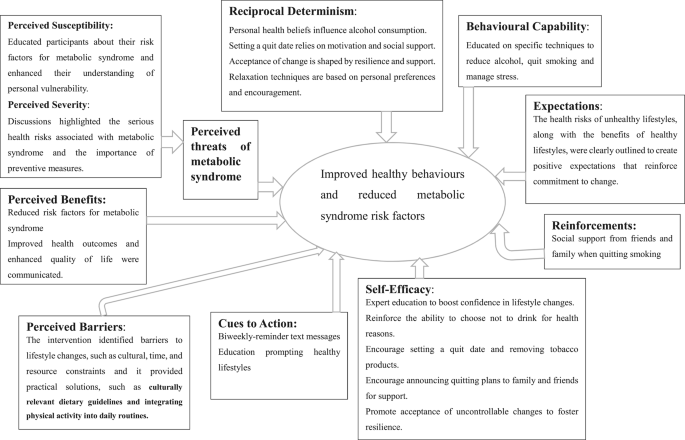

This trial offers strong evidence regarding the effectiveness of a workplace-based healthy lifestyle intervention in reducing the metabolic risk factors and promoting healthy behaviours in low-income country contexts. The findings will serve as valuable input for the design and implementation of future workplace health intervention programs, both in similar contexts and beyond.

The study found significant reductions in key metabolic syndrome risk factors in the intervention group, including WC, SBP, DBP, T. Chol, and LDL-c, compared to baseline measurements.

These findings align with previous workplace based interventions, including a study among university staff in Jimma, Ethiopia31, studies in Taiwan32 and from Iran, which reported reductions in WC and T.CHOL levels33.

The findings of our study demonstrate that workplace health education intervention effectively reduces metabolic syndrome risk factors and improves lipid profiles. The significant decreases in these biomarkers underscore the critical role of structured health education programs in reducing the prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Thus, this study supports workplace health initiatives as a valuable strategy for preventing chronic diseases. The control group also showed modest changes in metabolic risk factors from baseline measurements. However, these improvements were less pronounced than those observed in the intervention group, even with some increments in TGL levels. This outcome suggests that essential health interventions such as providing general health advice, conducting screening activities, and informing participants about their health status effectively reduce metabolic syndrome risk factors. Thus, continuous workplace health screening and education that motivate individuals to adopt healthier lifestyle practices are important in preventing the development of metabolic syndrome, even in the absence of structured, in-depth programs, as trialled in this study.

Despite the significant changes in the above risk factors, the intervention did not yield significant improvements in TGL and FBG levels, and an unexpected reduction in HDL levels was observed. These observations align with findings from other studies. One study34 noted that TGL levels remained unchanged post-intervention among participants receiving the similar intervention. Another study conducted in Iran noted a decrease in mean HDL-C levels along with a rise in FBG levels among the intervention group33.

Understanding the mechanisms behind the insignificant changes in TGL, FBG, and the unexpected decrease in HDL-c is crucial for guiding future interventions. The decrease in HDL-c is particularly noteworthy, as it is generally regarded as a protective factor for cardiovascular disease. Several factors likely contributed to these outcomes, including dietary focus, carbohydrate consumption, metabolic adaptations, impact of rapid weight loss, exercise variability, and the duration of the intervention. The intervention aimed to reduce overall fat intake but did not sufficiently prioritise the replacement of unhealthy fats with healthier options, which may have limited potential benefits on HDL-c levels. Participants also failed to significantly reduce their consumption of sweets and high-carbohydrate foods (injera, bread, rice, and noodles), which can lead to increased TGL and FBG levels while lowering HDL-c35. Metabolic adaptations in response to variations in energy intake or expenditure may have impeded improvements in HDL-c36, as individuals lose weight or modify their dietary patterns, the body can undergo metabolic changes that initially disrupt lipid profiles. These adaptations may encompass alterations in liver function as well as modifications in the synthesis and clearance of lipoproteins37,38. Insufficient improvements in insulin sensitivity may result in minimal changes in FBG and TGL due to increased triglyceride production37,39. Rapid weight loss can also raise TGL by mobilising fatty acids from adipose tissue, negatively impacting HDL levels39,40. Furthermore, variations in exercise intensity and type may yield different effects on HDL-c levels, particularly if participants engaged in high-intensity workouts without adequate recovery or nutrition41.

Lastly, the duration of the intervention may not have been long enough to achieve significant improvements in lipid profiles and blood glucose levels, underscoring the need for longer interventions to foster meaningful lifestyle changes and metabolic adaptations. To address these challenges, future interventions should emphasise balanced dietary guidance that includes healthy fats and educating participants about the sources of these foods. Implementing gradual weight loss strategies is important to minimise rapid metabolic changes, allowing for more stable adaptations and the maintenance of HDL-c levels. Tailored exercise programs should be designed based on individual fitness levels, incorporating a mix of aerobic and resistance training to optimise improvements in lipid profiles. Additionally, regular monitoring of lipid levels throughout the intervention provides valuable feedback; if HDL-c levels decrease, adjustments can be made in real-time to dietary and activity recommendations.

Moreover, extending the duration of interventions is crucial for facilitating transformative lifestyle changes that reshape dietary choices, ultimately leading to lower TGL levels and improved insulin sensitivity.

The difference-in-difference analysis indicates that the mean levels of T. Chol, knowledge acquisition, and consumption of fruit and vegetable portions exhibited statistically significant differences in the intervention group compared to the control group. Furthermore, at the end of the intervention, significant enhancements in fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity engagement were observed relative to the control group.

These findings suggest an optimistic path: extending the duration of the intervention could yield even more significant improvements in risk factors linked to metabolic syndrome. The increase in knowledge, coupled with substantial behavioural changes in dietary practices and physical activity, serves as a foundation in the transformation of metabolic health.

On the other hand, no significant changes were detected in participants’ attitudes, stress management, or the reduction of alcohol consumption. Several factors may account for these non-significant changes.

Modifying one’s attitude is an inherently gradual process that typically requires sustained effort over time to establish42. The ongoing political conflict between the federal government and the Amhara Fano (the armed force struggling for freedom) exacerbates stress levels by disrupting financial systems and fostering insecurity. At the same time, regular physical activity remains unfeasible without a contextually aware approach for home and workplace exercises. Our previous qualitative study (under review) highlighted that security concerns significantly hinder outdoor physical exercise.

This situation highlights the negative impact of political instability on public health, as it increases the risk of chronic conditions by hindering the adoption of healthy lifestyles. Context-specific interventions, such as home-based exercise programs, may effectively address these challenges and help prevent chronic diseases in these circumstances.

The assessment of alcohol consumption focused on participants’ experiences over the past seven days, coinciding with the Ethiopian New Year and a True Cross holiday, when social gatherings typically increase alcohol intake43. This cultural context likely contributed to the non-significant reduction observed. Additionally, unmanaged stress may lead individuals to consume more alcohol as a coping mechanism44.

This randomised controlled trial provides crucial evidence on the effectiveness of a contextually tailored workplace health education intervention in reducing metabolic syndrome risk factors and fostering healthier lifestyles in low-income settings. Although the effectiveness was tested in Ethiopia, it is applicable to other nations going through health transitions brought on by fast urbanisation and the switch from physically demanding agricultural work to sedentary, high-stress office work. These revelations support the global efforts that try to prevent NCDs. Policymakers should prioritise the creation of health-promoting workplace environments by developing and implementing structured workplace health intervention programs. Additionally, implementing general health advice, including regular health screenings, is essential to address the increasing burden of metabolic syndrome and related NCDs. Future studies should look at these interventions’ long-term effects on health outcomes, as well as their scalability and sustainability in a variety of working contexts. This will guarantee that successful strategies may be modified and used in diverse settings to improve public health worldwide.

A key strength of this study is its focus on low- and middle-income countries, assessing knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported behaviors related to diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and stress management, rather than solely measuring the effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle education intervention for metabolic syndrome risk reduction among office workers. The study is not without limitations and it is important to acknowledge those limitations. First, we employed a cluster randomised controlled trial design, which has inherent limitations due to intra-cluster correlation. Individuals within the same cluster may share similarities that can lead to correlated outcomes, causing standard errors to be underestimated and inflating the risk of type I errors. This correlation can diminish the apparent effectiveness of the intervention, as the outcomes may not reflect true differences between groups. To mitigate these effects, we utilised statistical methods such as generalized estimating equations, which account for the clustering. However, it is important to note that more participants may be required to achieve the same statistical power as individual randomisation due to the reduced effective sample size associated with clustering. Therefore, careful planning for a larger sample size during the study design phase is crucial to ensure adequate power and robustness of the results.

Second, the data on healthy lifestyle behaviors were collected through self-report methods, which are susceptible to various biases. These include social desirability bias, where participants may overreport positive behaviors, and recall bias, where they may struggle to accurately remember past behaviors. Additionally, response bias can occur if participants provide answers they believe are expected rather than their true behaviors. To enhance the reliability of future study findings, we recommend using objective measures, such as pedometers and food diaries with cross-checking, alongside self-reported data. Providing training for participants can also help improve the accuracy of their self-reports and reduce biases. Third, there is a potential for information contamination between groups, as complete control over this factor is challenging due to the intervention’s nature.