Participants

During the 2023–2024 school year, participants were recruited from Ordu University Düüriye Çetinceviz Preschool located in Ordu, a city in northern Türkiye, after obtaining the necessary approvals from the Directorate of National Education and the school administration. The sample consisted of 45 preschool students (20 girls and 25 boys) aged between 60 and 72 months, with an average age of 62 months, along with their parents. This study employed a semi-experimental design in which classrooms were not randomized but rather allocated to the intervention or comparison condition based on school administrative scheduling and teacher availability in collaboration with the Directorate of National Education. To minimize any selection bias, classes were established according to class size, age, and gender distribution. To reduce instructor-related variability, all sessions utilized similar materials and methods across classrooms. Due to the study employing a one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design, baseline equality among groups was not relevant. Internal validity was enhanced by employing the identical measuring equipment at both time intervals, guaranteeing uniform administration protocols, and regulating any confounding factors in the study. Four preschool classes were selected for this study.

The sample size was calculated in G*Power statistics software (paired-samples t-test, two-tailed) using an effect size = 0.45 derived from Hassanzadeh-Rostami et al. (pre: 6.34 ± 1.84; post: 7.08 ± 1.53; n = 23), with α = 0.05 and power = 0.80 [22]. The inclusion criteria for children aged 60–72 months with no chronic and/or psychological diseases and no diagnosis of eating disorders who complied with joining the study were included in the research. To carry out this research, “Ethics Committee Approval” was received from the Ordu University Social and Humanities Research Ethics Committee (number of meetings: 14, decisions: 2022 − 187, date: 27.10.2022). We conducted the research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [23]. The informed consent form was provided to the teachers and sent to the parents through the children. Each child’s carer or parent filled out a questionnaire developed by researchers and provided a signed informed consent form. The researchers also obtained the verbal consent of the children.

Instrumentation

Data were collected using a questionnaire that included sociodemographic characteristics of parents (i.e., age, education level, work, and economic level) and children (i.e., age and sex), anthropometric measurements of children, and the Preschool Children’s Nutrition Screening Tool (NutriSTEP®).

Anthropometric measurements

The height (in cm) of children was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm while the child was standing with their head and chin up, looking straight ahead (i.e., held in the Frankfurt plane) using a stadiometer (telescopic height meter) [24]. Children’s body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg without shoes and in light clothing using the Tanita BC 601 Golden Inner Scan (Balance™) [24]. The body mass index (BMI) for age z-scores (BAZ) was computed using WHO AnthroPlus software (version 1.0.4, February 2011), using the World Health Organization’s growth standards [25]. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2007) growth standards and the WHO AnthroPlus software (version 1.0.4, February 2011) program were used to calculate Z-scores [26].

Preschool children’s nutrition screening tool (NutriSTEP®)

NutriSTEP® is a community-based nutritional screening tool designed to assess the nutritional risk of preschool children. The tool, developed by Randal Simpson et al., involves parents in its delivery [27]. NutriSTEP® questionnaire evaluates various aspects of the children’s health, including dietary habits, physical maturation, physical activity, sedentary behavior levels, food safety, and nutrition-related environments. Each question in the questionnaire has a range of options, and a score of 0 to 4 is assigned to each choice, with the total points being calculated by adding up the points given for each question [27]. The Turkish validity and reliability of this 16-item scale was conducted by Pulat Demir and Turgut [28]. The scale’s cut-offs are ≤ 27 for low risk, 27–31 for moderate risk, and > 31 for high risk. NutriSTEP® is a reliable and effective tool for assessing the nutritional risk of preschool children, providing valuable insights into their health and well-being.

Materials

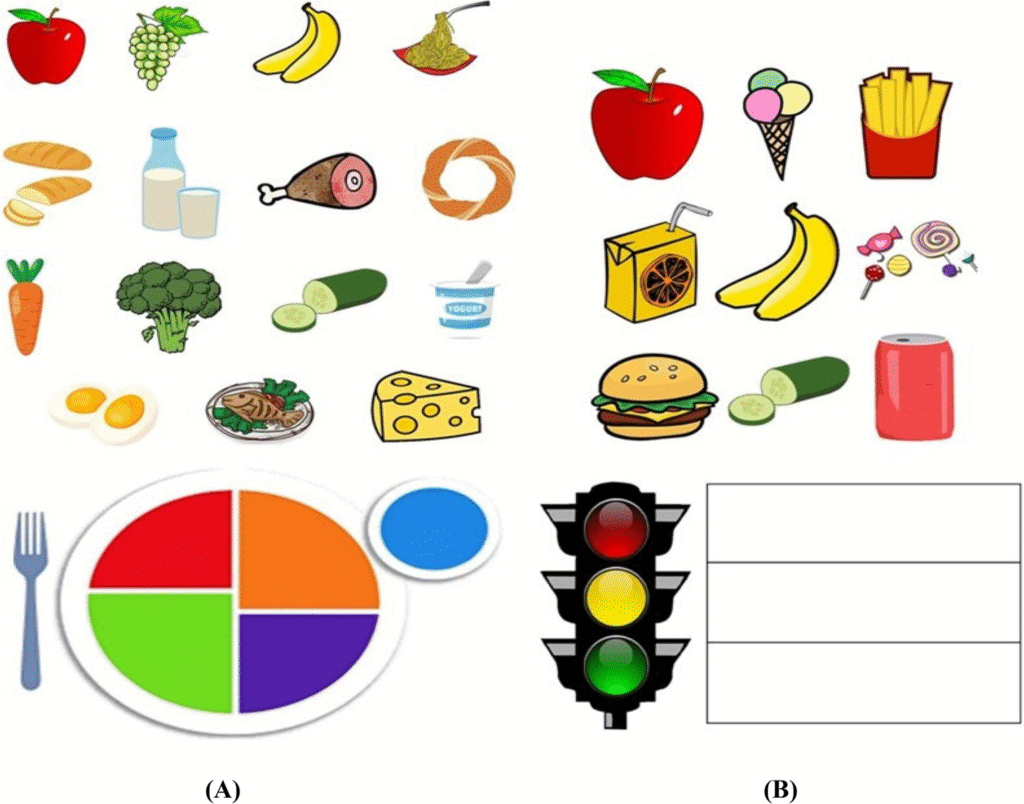

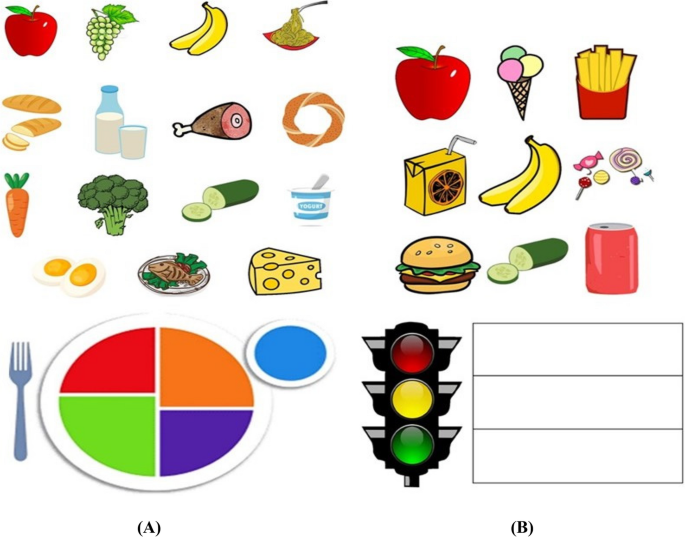

Children’s knowledge of food groups and their preferences was assessed using interactive, age-appropriate visual food cards. Food item cards designed in a game-like design were used as stimuli [29]. The food cards included in this study were meticulously crafted to be developmentally suitable for preschool-aged children. The pictures were made simple, colorful, and culturally pertinent to the participants’ nutritional environment, ensuring that children could readily identify and distinguish between food items. The content validity was established by modifying the food examples to align with the widely consumed foods of the research population, so improving both ecological validity and the instrument’s comprehensibility for this specific age range. For this study, the same instruments were administered at the start of the nutrition education intervention (pre-intervention) and four weeks later (post-intervention) to evaluate the children’s knowledge. In the pilot study, the children received 32 food cards but seemed tired because selecting and gluing them took over 20 min. The number of food cards was reduced to 24 to allow children to complete the study carefully. The first instruments contained fifteen food cards (i.e., apple, meat, bread, broccoli, and milk), including three food cards for each of the five food groups and one colored MyPlate picture. The second instrument contained nine different food cards (i.e., banana, French fries, and ice cream), including three food cards for each traffic light color and one for a colored traffic light picture. The materials were developed based on the “MyPlate for Preschoolers” [30] and Wendy Cooper’s “Healthy Highway Program” [31], and were culturally adapted with locally familiar foods and age-appropriate terminology to ensure suitability for preschool children in Türkiye. The 24 food cards were carefully chosen to represent various food groups and levels of familiarity among the participants in the study. The instruments comprised food often consumed by students at school and home. Materials are given in Fig. 1.

Procedure

A semi-experimental design with a pre-and post-test pattern was utilized for this study. A semi-experimental design is a research methodology that imitates experimental studies by influencing an independent variable and employing pre–post measurements, yet it does not incorporate random assignment. This approach serves as a practical alternative when true experiments are impractical, though it presents certain limitations concerning causal inference and internal validity. Research studies commonly utilize pre-test and post-test data to assess the impact of educational programs, health interventions, or legislation [32].

The nutrition education was administered in four classes over 4 weeks in the winter of 2024. Educators present recruitment scripts to preschoolers to clarify involvement in the program. Students took home forms for parents to sign and provide student assent, which students returned to school for the teacher to collect. Assented students took written pre- and post-assessments evaluating the nutrition education program.

Researchers conducted a thorough literature review to gather information necessary for developing a nutrition education intervention tailored to specific behaviors and sensitive to cultural factors. The content prepared was presented to experts for their opinion, and the final version was developed based on expert opinions, including an associate professor doctor from the Preschool Education Department, two associate professor doctors from the Nutrition and Dietetic Department, and a preschool educator. The Provincial Directorate of National Education and the directors of the applicant schools assessed the educational material for its suitability for preschool children and concluded that it was appropriate.

The nutrition education curriculum for children highlighted the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) MyPlate for Preschoolers [33], the Healthy Highway Program [31], and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [34] guidelines;; although the curriculum was not formally pilot tested prior to implementation, its content was adapted from established, evidence-based sources. The nutrition education program included four topics: Nutrition and Health, MyPlate Knowledge, Health on the Road, and Healthy versus Unhealthy Foods. Each week of the program focused on a different topic. The nutrition education program was conducted during four weekly sessions, each lasting 30 min, during school hours. An experienced researcher conducted the sessions utilizing PowerPoint slides and a computer-assisted projector. Diverse pedagogical techniques, such as role play, exercises, games, posters, and ancillary materials, were utilized to actively include children. The content of the nutrition education intervention is shown in Table 1.

Each child had one-on-one interviews in an isolated room supervised by educators. Each interview had a duration of approximately 20 min. The child sat at a table facing the interviewer. Fifteen food cards and a visual plate icon were presented during the initial phase. The child was instructed to categorize three food cards based on their perceived similarity and stick them to a plate model using hypoallergenic glue. Nine food cards and a visual traffic light icon were presented during the second stage. The child was given directions to categorize three food cards based on the traffic light, determine the corresponding food card to one of the three colors (red/yellow/green), and stick them using hypoallergenic glue. Following the task, the interviewer asked if the child desired to change the arrangement of the cards. After each session, a visual plate and traffic light icon with completed groups were photographed and recorded if no further changes were made. Applications were conducted twice before the nutrition education and again in the fourth week post-education.

Data analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Visual (histogram and probability graphs), skewness/kurtosis, coefficient of variation, detrended plot, and Shapiro Wilk/Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were conducted to determine whether the data were normally distributed [35]. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are expressed as frequency (n) and percentage (%).The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed that the data conformed to normality assumptions, indicating a normal distribution. For quantitative variables, a paired Student’s t-test was applied, while the McNemar test was used for qualitative variables to assess changes following the nutrition education intervention. In addition, children’s responses regarding each food item in the MyPlate and Healthy Highway Program were categorized as either two or fewer correct responses or more than two correct responses. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.