Stronger Together was a single-arm feasibility study with pre-post intervention measures conducted at AlNahda Society in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The design was appropriate for investigating the feasibility and potential efficacy of an innovative intervention to increase physical activity and healthy diet in low-income women [17]. This study was implemented in preparation for a large-scale, randomised, controlled trial to assess the long-term intervention outcomes. Ethical approval for the study was received from King Saud University Human Research Ethics Committee (KSU-HE-23-482). We followed the CONSORT guidelines for reporting pilot and feasibility trials (Supplementary file 1).

The study was conducted in collaboration with AlNahda Society, a non-profit organisation dedicated to empowering women socially and economically in Saudi Arabia [18]. AlNahda Society works to achieve its mission by assisting low-income households in graduating from poverty by addressing unmet needs. They provide their beneficiaries with career education and capacity development to equip them with the skills to become active contributors to the development of Saudi society [18].

Stronger Together intervention development

We followed the Medical Research Council guidance for the development and evaluation of complex interventions [17] and we used the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) to guide the design of the behaviour change intervention [19].

Intervention theoretical framework

There is an increasing recognition that behaviour change theories should inform and support the development of behaviour change interventions [17]. By understanding the theoretical mechanism of change, interventions will target causal determinants of behaviour. This may facilitate understanding the reasons behind an intervention’s effectiveness or lack of effectiveness [20]. The BCW consists of layers of components to consider for supporting behaviour change, including the determinants of behaviour (Capability Opportunity Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) model) and intervention functions [19]. The COM-B model suggests that for a health behaviour to change, change is required in at least one of three components: an individual’s capability to perform the behaviour, the opportunity for the behaviour to occur, and motivation to perform the behaviour [21]. We initially used the COM-B model to explore barriers and facilitators to physical activity and healthy diet among low-income women [22]. Then we developed an intervention targeting these factors and theoretical components. We followed the BCW intervention design stages to develop the intervention.

In the first stage, the focus was on understanding the target behaviour. The intervention aimed to promote healthy eating and physical activity. We conducted a qualitative study to identify key factors for facilitating behaviour change among the target group [22], drawing also on previous evidence relevant to this population [15, 23]. In the second stage, we aimed to identify intervention options. Based on the factors identified in the first stage, we selected intervention functions from the BCW that would effectively support behaviour change [19]. The chosen functions included education, training, modelling, enablement, persuasion, and environmental restructuring. In the third stage, we aimed to identify the content and implementation options for the intervention.

We identified behaviour change techniques from a taxonomy of 93 techniques [24], selecting those that best matched the intervention functions and previous findings [25,26,27,28,29]. Supplementary Table 2 provides a mapping of behaviour change techniques associated with the COM-B model and intervention functions. The intervention combined face-to-face group sessions and virtual communication, preferred by the target group [22]. Face-to-face sessions at the AlNahda Society provided space for physical activity and interactive discussions.

Description of intervention

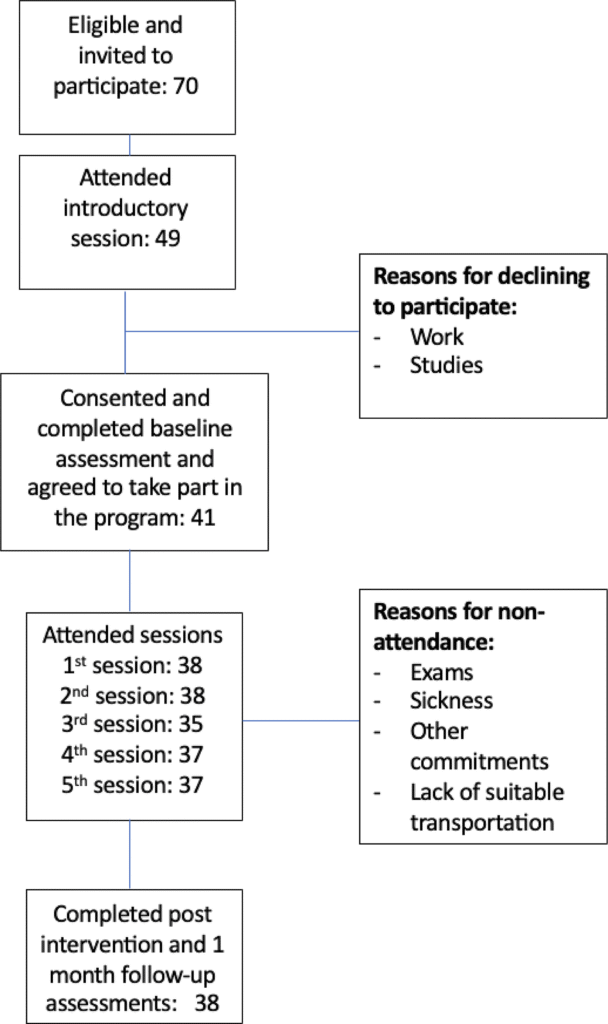

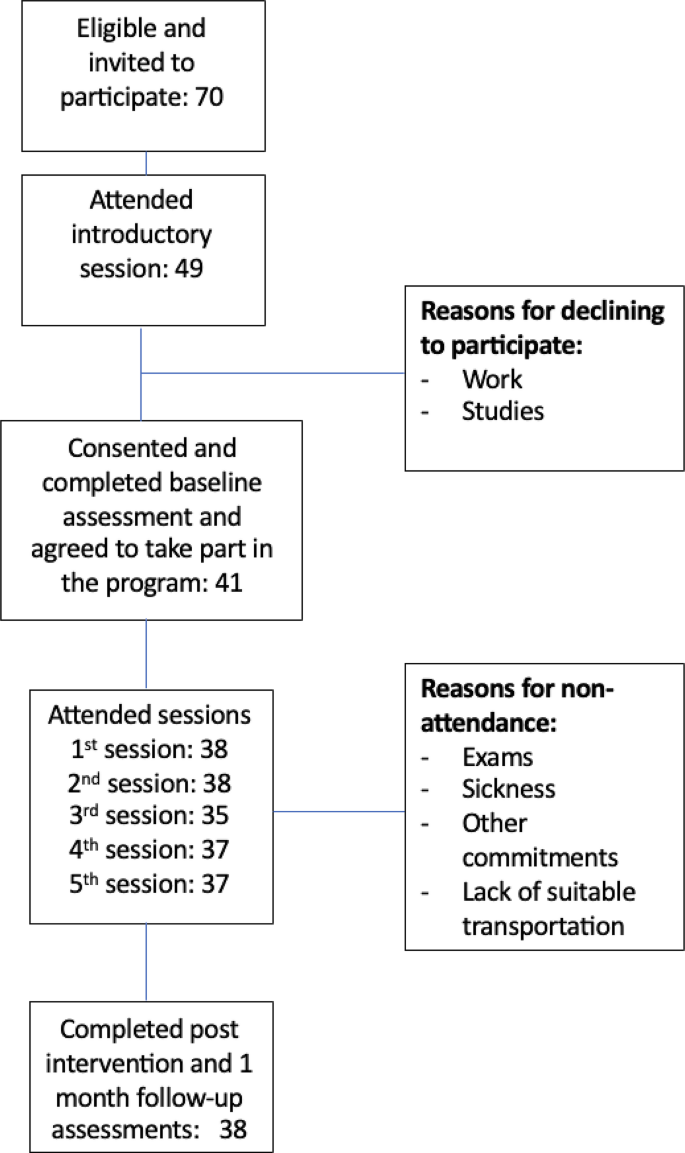

The intervention lasted five weeks, and participants were followed up one month after completion (See Fig. 1). The intervention aimed to help participants use readily available resources and adopt healthy lifestyle changes in their daily routines. It involved two-hour face-to-face sessions each week and daily virtual support. The virtual support included an online chat group using WhatsApp. Additionally, one of the weekly meetings was held virtually (via Zoom) based on the participants’ preference, as it coincided with school holidays. Attendance at the virtual session was comparable to face-to-face sessions (see Fig. 1).

The intervention team consisted of health mentors, intervention providers, and assessors. Health mentors supported participants in their behaviour change journey. They had a health education or nutrition background and/or training in behaviour change techniques. Intervention providers delivered the weekly sessions and included clinical nutrition and physical activity specialists.

In the intervention, each participant was matched with a health mentor, with each mentor responsible for 8–10 participants. The mentors met with the participants at the program’s start to set health goals and track and support their progress. Additionally, participants were provided with Fitbit wearable activity trackers to monitor and share their physical activity. Studies have shown that wearable activity trackers can effectively increase physical activity levels across different groups, and these changes are sustainable over time [30]. Participants were encouraged by mentors to join the WhatsApp group to share progress, challenges, or questions. They took pictures of their Fitbit daily steps to share. Every Sunday, a health topic was discussed based on participants’ interests and needs. Participants competed weekly to achieve the highest steps, encouraging behaviour change. Compliance with the weekly competition was not monitored, as it was a behaviour change technique. Table 1 includes an overview of the intervention.

Mentors’ fidelity to the intervention protocol was monitored and supported through various methods. Each mentor completed a checklist of steps for each participant to ensure consistency, and the project manager was present in all WhatsApp groups to guarantee a similar level of encouragement and facilitate discussion of topics. The project manager also provided support to the mentors and ensured the intervention was delivered consistently.

Participants and recruitment

We recruited participants from AlNahda Society, intending to enrol at least 30 women for the pilot intervention, in line with recommendations for a reasonable sample size for pilot studies [31]. The proposed sample size will provide feasibility data to determine the sample size for a future fully-powered trial [31]. The eligibility criteria were women over 18 years of age, AlNahda beneficiaries, and capable of committing to the intervention. Participants were excluded if they were involved in any other lifestyle behaviour change intervention or if they were pregnant or postpartum women.

The intervention team provided AlNahda staff with details and an information sheet about the intervention. Based on the inclusion criteria, AlNahda staff identified potential participants from their existing clientele. Case workers from AlNahda Society contacted their list of beneficiaries to explain the programme and assess their initial interest in participating. Mothers and their daughters (over 18 years old) were invited to join as a group. Young children (under the age of 18) were not included in the intervention, nor were their mothers provided with accommodations as part of the intervention. The intervention team contacted potential participants by phone for initial screening to reconfirm their eligibility and further explained the intervention. After initial recruitment, participants were invited for an introductory session in AlNahda facilities (Table 1). The session involved introducing participants to the intervention and team, obtaining informed consent, and conducting the baseline assessment.

Measures

We examined the feasibility of our recruitment criteria regarding screening and enrolment in the intervention, intervention completion rate, and attendance and engagement with the intervention. The acceptability of the intervention was also assessed using qualitative methods with both intervention providers and participants, and the results will be reported separately. In the qualitative evaluation, we examined participants’ acceptability of intervention components, including in-person and virtual sessions, support, mentorships, Fitbit, self-monitoring, and behaviour change experiences. Assessors were independent of the intervention delivery team, had a clinical nutrition or epidemiology background, and were trained to conduct assessments.

Socio-demographic information

At baseline, a demographic face-to-face questionnaire was completed for each participant for descriptive data. The questionnaire included questions on participants’ age, educational level, marital status, employment status, and number of children (if applicable).

Intervention adherence

The number of face-to-face sessions attended and reasons for lack of attendance were monitored and reported. Participants were offered a transportation subsidy to facilitate attendance and reduce any financial barriers. Mentors sent reminders to all intervention participants to encourage attendance in the weekly sessions.

Adherence and engagement to online behaviour change interventions using social media platforms could be measured using different methods to assess the continuity and intensity of participant engagement [32]. We measured participants’ engagement with WhatsApp groups by tracking the number of posts per participant per week and the number of participants who shared their step counts on a weekly basis. Previous evidence suggested considering 70% engagement in digital platforms as “good” adherence [32].

Health-related outcomes

Health outcome assessments included weight in kilograms (kg), dietary behaviour, physical activity, mental health, and quality of life. These outcomes were evaluated at baseline, right after the intervention (i.e., post-intervention), and one month later. The baseline and post-intervention assessments were conducted in AlNahda facilities, while the one-month follow-up assessment was conducted over the phone. Participants were given a 100 Saudi Riyals gift voucher to complete the assessment at each time point.

Weight

Weight was measured using a digital floor scale (SECA 769 Clinical Scale) at baseline and post-intervention, and height was measured using a portable stadiometer at baseline. For the one-month follow-up over the phone, participants were advised to visit the pharmacy or use a home scale to measure their weight. We measured changes in weight (kg) and body mass index (BMI) across the entire sample, then analysed weight change by BMI category. To calculate BMI, we divided participants’ weight by their height squared. The sample was classified according to their BMI level, and weight changes were examined for each category.

Physical activity

We assessed participants’ physical activity levels using the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) at baseline, post-intervention and one-month follow-up, and we used the official Arabic version of the tool [33]. The IPAQ was developed to standardise population-level activity surveillance worldwide [34]. The short version of the IPAQ consists of four dimensions of physical activity: vigorous physical activity, moderate physical activity, walking and sitting time. Physical activity MET-minutes were calculated based on the methods outlined in the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) analysis guidance [35].

Diet

Diet was assessed using 24-hour dietary recalls for two days. The dietary data were collected face-to-face on the first day for the baseline and post-intervention assessments, and on the second day, they were collected over the phone. For the one-month follow-up, both days were collected over the phone. We used ESHA Food Processor Nutrition Analysis Software to analyse the dietary data. The software calculates each individual’s average intake of food groups such as fruits and vegetables. Recipes of mixed dishes and traditional Saudi foods were manually added to the software. We used average portions of fruits and vegetables to measure dietary behaviour.

Mental health

We used the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) to assess mental health outcomes. K6 is a simple measure of psychological distress involving six questions about an individual’s emotional state [36]. Responses were totalled to generate a composite score (ranging from 6 to 30), where higher scores indicate increased distress. We used a validated translated Arabic version of the scale [37].

Quality of life

We used the World Health Organisation Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire. The tool consists of 26 items that assess four quality of life domains: physical health, psychological health, social relations, and environment [38]. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores corresponding to better quality of life [38]. We used the Arabic version of the tool, which has been tested for validity and reliability among Arabic-speaking participants [39].

Data analysis

The participants’ baseline characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges. Given that the data for most outcomes were not normally distributed, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test, non-parametric statistics were employed. The Friedman test was used to compare (weight, diet servings, K6 score, WHOQOL domains and physical activity) between baseline, post-intervention, and one-month follow-up. These outcomes included continuous variables (weight, diet servings, physical activity) and composite scores from questionnaires (K6 score, WHOQOL domains). Statistical significance was set at p < .05, and the overall effect size was reported using Kendall’s W. If significant differences were found, post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni correction were used to evaluate pairwise comparisons between time points. For these corrected tests, a p-value of less than 0.017 indicated statistical significance, and the effect size for each comparison was reported using the matched-pairs rank-biserial correlation (r). This adjustment corresponds to the three comparisons performed within each outcome variable, and the correction was applied separately for each outcome to control for Type I error while maintaining interpretability. A complete-case analysis was conducted, with participants excluded from a given analysis if data for that outcome were missing at any time point. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 [40].