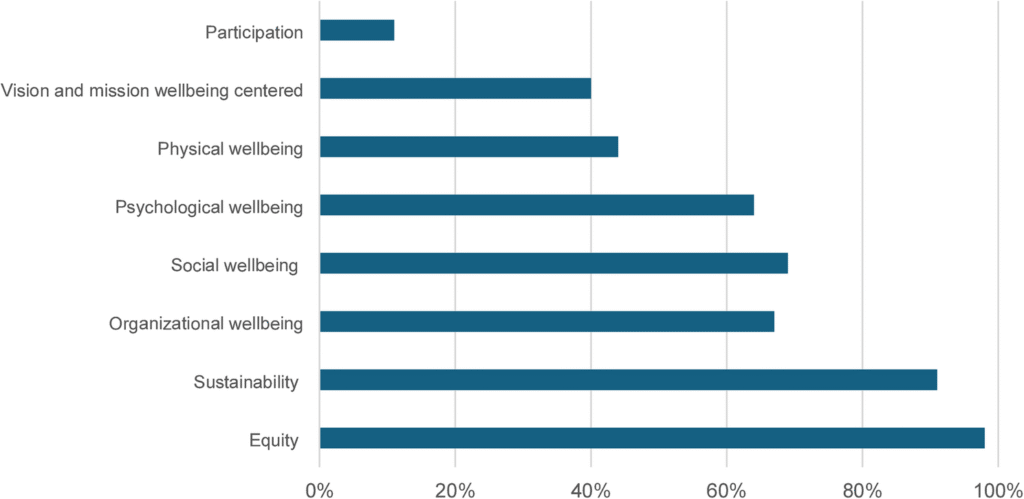

The Okanagan Charter outlines the key principles for making a university a healthy setting for students, faculty, and administrative staff. It emphasizes the importance of fostering supportive environments to promote wellbeing across multiple dimensions – physical, social, mental, and organizational – as well as strengthening individual capacities. It also highlights the role of active participation in cultivating thriving communities and calls for a strategic reorientation of services to enhance accessibility and sustainability. In the present paper, these foundational principles were applied as thematic categories in the content analysis. The analysis of strategic plans from Italian state universities enables a comprehensive understanding of the extent to which health promotion is integrated into institutional policies, while also facilitating the identification of the specific dimensions of health and wellbeing that are most prominently addressed.

While participation is a fundamental pillar of health promotion, it still holds a marginal role in the strategic plans of Italian public universities. Only a limited number of institutions have initiated authentic participatory processes that fully engage the academic community in the development of strategic plans—enabling meaningful contributions to the formulation of objectives, the definition of strategies, and, ultimately, the decision-making process [16]. Adopting a bottom-up participatory approach in the development of strategic plans can foster empowerment and a sense of ownership, while also enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of the actions undertaken [15, 17]. The findings of this study provide concrete examples of participatory dynamics in the development of strategic plans and call on Italian universities to recognize and embrace the transformative potential of participation by integrating it as a structural element within their strategic and decision-making processes.

Equity and sustainability emerge as recurring themes, reflecting a strong and ongoing commitment that originated from the establishment of the Network of Universities for Sustainable Development (RUS) in 2016 by the Conference of Rectors of Italian Universities (CRUI), which was created to foster inter-university collaboration on environmental and social responsibility. Additionally, the National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (ANVUR) has incorporated contributions to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 2030) into its evaluation criteria, further reinforcing the institutional relevance of these principles.

Strategic plans consistently consider equal opportunity issues, including gender and socio-economic disparities, support for students with disabilities, and the inclusion of marginalized groups. However, the measures implemented do not always ensure full equity. For instance, tax relief for low-income students is frequently tied to merit-based criteria—likely a consequence of constrained public funding. This approach may undermine equity goals, as students from disadvantaged backgrounds often face systemic barriers that impede academic performance.

In terms of sustainability, most objectives and actions focus on energy efficiency, sustainable mobility, and waste management. However, sustainable nutrition is notably underrepresented, appearing in the plans of only four universities. This suggests a growing but still sectoral integration of sustainability across university policies. Although university canteens are typically managed by Regional Authorities for the Right to University Education, universities—through their representatives—should assume a more active advocacy role in promoting sustainable dietary practices. Such engagement would support the development of a holistic, campus-wide culture of sustainability.

A noteworthy observation is that references to equity and sustainability are often absent from initiatives aimed at promoting psychological, physical, social, and organizational wellbeing. This indicates a compartmentalized approach, where these principles are treated as separate domains rather than foundational elements embedded across all aspects of university life.

Physical wellbeing is primarily addressed through organized sports activities, while informal physical activity—such as the creation of pleasant spaces for walking or relaxation during study and work breaks—is sporadically considered. Only a minority of plans recognize sport as a means of fostering social interaction. Other health-related areas, such as nutrition, smoking and alcohol remain largely overlooked, further highlighting a fragmented approach to holistic wellbeing. Collaboration with the National Health Service remains largely underdeveloped, despite the high potential of the university setting for primary and secondary prevention interventions targeting young and adult populations—groups that are often difficult to reach through conventional healthcare channels [18]. The call to establish local partnerships between universities and health services remains highly relevant, particularly in addressing priority public health issues such as alcohol use and sexual health [19, 20].

Regarding psychological wellbeing, institutional strategies are predominantly reactive, focusing on the provision of counseling services—typically limited to students. This narrow scope fails to address the broader needs of the academic community and overlooks faculty and staff, whose mental health is equally critical. A more effective approach would adopt a preventive and health-promoting perspective, fostering conditions that support mental wellbeing and flourishing for all university members [21]. Regarding students, several areas for intervention are highlighted by the BM84 Resolution on Italian Students’ Mental Wellbeing, which emphasizes the urgent need to address the intense academic pressure, competitive environment, and the unrealistic expectations perpetuated by prevailing narratives around university success. Additionally, the document highlights students’ need to be actively involved in the dialogue aimed at re-evaluating teaching methods, academic pathways, and assessment practices, emphasizing how participation is perceived as essential and closely linked to mental wellbeing [22]. About employees’ psychological wellbeing, recent studies highlight the crucial role of job satisfaction, work engagement, employment stability, career development opportunities, and a supportive and peaceful work environment [23,24,25,26].

In Italian universities’ strategic plans references to organizational wellbeing are often generic and lack operational detail. Concrete actions typically concern remote working arrangements, parental support, welfare measures, and monitoring of stress and burnout. Only in a few cases are initiatives explicitly mentioned that aim to strengthen organizational capacity to promote wellbeing during working hours, suggesting a limited awareness that time spent at work should also be experienced as time of wellbeing. Universities should address the challenge of employee wellbeing by encouraging research focused on the development of supportive policies, including workload management, mental health services, and opportunities for recognition and professional growth [27].

Social wellbeing is generally promoted through support for student associations and the organization of cultural and sports events. Nearly half of the universities demonstrate awareness of the importance of providing green or indoor spaces to facilitate everyday social interaction. However, only a limited number of plans approach sociality through the lens of equity and inclusion, with targeted initiatives aimed at enhancing the social academic life of people with disabilities.

Overall, the analysis of strategic plans outlines a growing yet fragmented commitment by Italian universities to integrating health promotion into institutional policies. Although references to health and wellbeing topics are present in strategic documents, these concepts often fail to translate into coherent and systemic interventions. Actions tend to be sectoral, targeting specific segments of the academic community, and are frequently reactive rather than preventive in nature. This result is fully aligned with international evidence, which highlights the widespread challenges universities face in effectively translating the theoretical concept of the ‘Whole System Approach’ into practical, integrated actions [28].

The fragmentation of the health promotion policies in Italian universities aligns with findings indicating that more than two-thirds of universities do not explicitly include health and wellbeing in their institutional mission and vision, while the remaining third address only selected dimensions. Without a clear and integrated recognition of these themes within the mission and vision, health and wellbeing are unlikely to be perceived as core elements of institutional identity. Consequently, their ability to guide strategic decision-making, influence resource allocation, and generate structured interventions remains limited. Furthermore, this could undermine efforts to establish wellbeing as a shared value among students, faculty, and administrative staff, and as a core component of the academic identity [15].

As research on Health Promoting Universities continues to work toward the development of an operational framework capable of moving beyond a purely theoretical approach, this study offers preliminary insights that may support institutions in initiating this transformative process. The identification of good practices for health promotion within the university setting —characterized by their practical, replicable, and often low-cost nature—is intended to support advocacy and the development of strategic plans that integrate health and wellbeing into the mission and vision, and, crucially, translate these principles into concrete actions. These practices are intended not only to inform policy development but also to serve as actionable tools for stakeholders committed to embedding wellbeing into the academic mission and culture.

The main limitation of this study is that, although references to policies, objectives, and actions related to the health and wellbeing of the university community were identified in strategic plans, we cannot confirm whether these actions were implemented, nor are we able to monitor their outcomes due to the lack of accessible data sources. Nevertheless, this limitation does not affect the value of our contribution. Rather than serving solely as an assessment of how Italian universities integrate health and wellbeing into their institutional strategies, this paper offers replicable practices that can be adapted by universities both nationally and internationally. Future research could complement the analysis of strategic plans by exploring additional sources of publicly available information, such as university websites and institutional communications, with a particular focus on campuses that showcase promising practices. This would allow for a deeper understanding of how strategic commitments to health and wellbeing are operationalized and communicated, and offer insight into implementation processes. Future studies might also include the analysis of third mission policies, strategies, and actions aimed at external stakeholders to assess the actual impact of universities’ commitments related to health and wellbeing on the community. This would offer insight into how universities can mobilize their academic and research capacities to foster wellbeing and equity beyond institutional boundaries.