Longevity should never mean simply surviving longer. The true measure of progress is adding life to years, not just years to life, write Shafi J Ahmed and Abdullah A Dewan

THE dream of living not just longer but healthier beyond the age of 70 has fascinated medical researchers, public health experts and ordinary people alike. Global life expectancy has risen steadily, particularly in countries where infectious diseases have been curbed and healthcare access has improved. Yet the real question is not simply how many years people live, but what quality of life they enjoy in those years. Scientific evidence now shows that older adults who adopt certain patterns of living can not only add years but fill them with vitality, clarity and purpose.

Family history matters, but far less than once believed. A study in the Journal of Gerontology found that individuals with parents who lived beyond 85 were more likely to pass that threshold themselves, suggesting that longevity does have a genetic anchor. Yet twin studies show heredity explains only 20–30 per cent of lifespan variance; the rest comes from lifestyle and environment. Epigenetics adds nuance: diet, exercise, and stress levels can ‘switch on’ or ‘switch off’ certain genes, showing that heredity is not destiny. In Bangladesh, where many elderly grew up under conditions of poverty and malnutrition, today’s younger generation has a greater chance to age healthfully if they adopt preventive habits early.

Exercise acts as a natural ‘polypill’, protecting against heart disease, diabetes, obesity, depression and even certain cancers. A study in The Lancet Public Health reported that older adults who engage in regular moderate activity — walking, cycling and swimming live longer with higher quality of life. Walking just 30 minutes daily can cut mortality risk by 20–30 per cent. Muscle preservation is particularly important. Sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss, undermines independence and increases falls. Resistance training with light weights or elastic bands helps prevent this decline. In countries like Japan, community gardening and daily walking are credited with sustaining some of the world’s longest lifespans. Bangladesh’s elders often lead sedentary lives, but simple adaptations such as group walking or yoga can help maintain mobility and independence.

What we eat often matters more than any pill. The New England Journal of Medicine highlights the Mediterranean diet — rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, fish and olive oil — as strongly associated with longer life and reduced chronic illness. Traditionally, Bangladeshi diets once resembled this model: lentils, leafy greens, seasonal vegetables and modest portions of fish. But in recent decades, urban diets have shifted towards fried foods, refined grains and sugary drinks. Nearly one-third of urban adults in Bangladesh are now overweight, while frailty remains common in rural elders. Both extremes increase health risks. Micronutrients are also critical: calcium and vitamin D reduce osteoporosis, omega-3 fatty acids protect brain health, and protein sustains muscle. For older adults, the principle is simple: eat enough, but not too much.

Depression and loneliness are often invisible, but deadly risks. A JAMA Psychiatry study found that late-life depression doubles mortality risk, partly by impairing heart and immune health. Conversely, strong social ties can extend life expectancy as much as quitting smoking. Harvard’s long-running Study of Adult Development found that close relationships are the single strongest predictor of healthy aging. Mental stimulation matters too: activities such as reading, learning new skills and problem-solving can delay dementia by years. Bangladesh retains a cultural advantage in its multigenerational households, where elders remain engaged in family life. Yet urbanisation and migration now threaten that tradition, leaving many older adults isolated. Community centres and volunteer networks could help restore purpose and belonging.

Preventive care is medicine’s quiet revolution. Regular screenings for hypertension, diabetes and cancer extend life by detecting disease early. A BMJ study found that controlling blood pressure in older adults can cut stroke incidence by as much as 40 per cent. Vaccinations, especially for influenza and pneumonia, significantly reduce mortality among the elderly. Yet in Bangladesh, preventive care remains underutilised. Many older patients seek medical help only after falling ill, while routine screenings are rare outside urban centres. Expanding access to preventive services could add not just years to life, but healthier years.

Sleep is often overlooked, but it remains a cornerstone of longevity. Harvard Medical School researchers confirm that older adults who maintain 7–8 hours of quality sleep enjoy stronger immunity, memory and cardiovascular health. Poor sleep from insomnia or sleep apnoea accelerates aging. Chronic stress is another silent driver of disease. High cortisol levels damage the heart and shorten telomeres, markers of cellular aging. Stress reduction through prayer, meditation, deep breathing or mindfulness can slow these effects. In Bangladesh, cultural practices such as daily prayer and yoga could be mobilised as low-cost solutions for stress management in old age.

Tobacco remains Bangladesh’s most preventable killer. More than one-third of adults use some form of tobacco, smoked or chewed. The American Journal of Public Health confirms that quitting smoking — even after age 70 — improves survival. At the same time, a new dietary threat is rising: sugary soft drinks. Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and similar beverages contribute to obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes. A Lancet Global Health study estimates that sugar-sweetened beverages contribute to nearly 200,000 diabetes-deaths globally each year. Reducing tobacco and sugary drink consumption is one of the simplest, most powerful strategies for extending healthy life in Bangladesh.

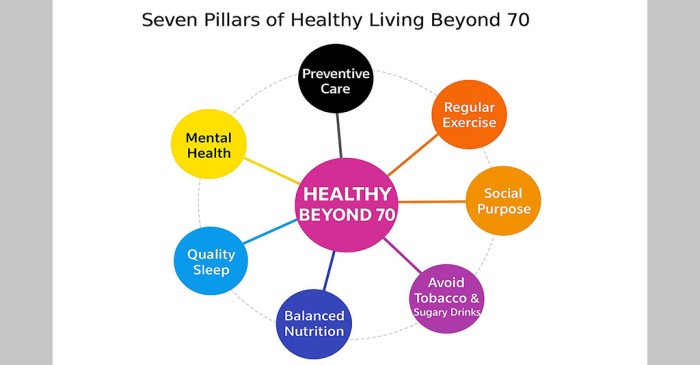

Older adults in Bangladesh face a heavy burden of chronic disease. Hypertension prevalence rose from about 21.5 per cent in 2011 to nearly 35 per cent in 2018. The 2018 STEPS survey reported national prevalence at 25.2 per cent. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affects around 12.5 per cent of adults, particularly those exposed to tobacco or biomass smoke. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death, while stroke and chronic kidney disease remain common. Environmental factors intensify these risks. Bangladesh is consistently ranked among the world’s most polluted countries, with fine particulate air pollution driving cardiovascular and respiratory illness. Arthritis and gastrointestinal disorders further limit mobility and nutrition. Yet many of these conditions are not inevitable. They are aggravated by preventable risks: poor diet, sedentary lifestyles, smoking, stress and indoor air pollution. The seven pillars of longevity — balanced diet, regular exercise, preventive care, mental health, quality sleep, avoidance of tobacco and sugary drinks, and strong social purpose — are practical tools that can turn the tide.

Living beyond 70 in good health is neither accident nor luxury. It is the cumulative result of choices by individuals and by societies. Genetics may set the stage, but daily habits, preventive healthcare and community support determine the outcome. For Bangladesh, the challenge is urgent. Policymakers must invest in smoke-free laws, clean cooking fuel, safe spaces for exercise, affordable screenings, and stronger community networks. For individuals, the message is equally powerful: eat wisely, stay active, sleep well, remain connected and reduce harmful habits. Even late in life, adopting these changes can yield dividends.

If we want more Bangladeshis to live well beyond 70 — not merely live long — we must act on what this evidence already makes plain: seven levers change the curve. A balanced diet, regular movement, preventive screening, emotional and cognitive wellbeing, restorative sleep, avoiding tobacco and sugary drinks, and a strong sense of social purpose work together like interlocking gears. Pull one lever and the others turn: neglect one and the whole system grinds. The cost of inaction is paid in hospital beds and shortened lives, but the return on simple, doable habits — walks, lentils and greens, check-ups, prayer or meditation, family and friends — is compounding health. Policies can make those choices easier; people can make them daily. That is how we add life to years, not just years to life.

Longevity should never mean simply surviving longer. The true measure of progress is adding life to years, not just years to life.

Dr Shafi Jakir Ahmed, MBBS (Dac), MD (USA), Flint, Michigan, USA. Dr Abdullah A Dewan is a former physicist and nuclear engineer at the BAEC and professor emeritus of economics at Eastern Michigan University, USA.